New research indicates a better understanding how cancer cells evolve from healthy brain cells and evade treatment could reveal potential new drug therapies for one of the most common and lethal brain cancers

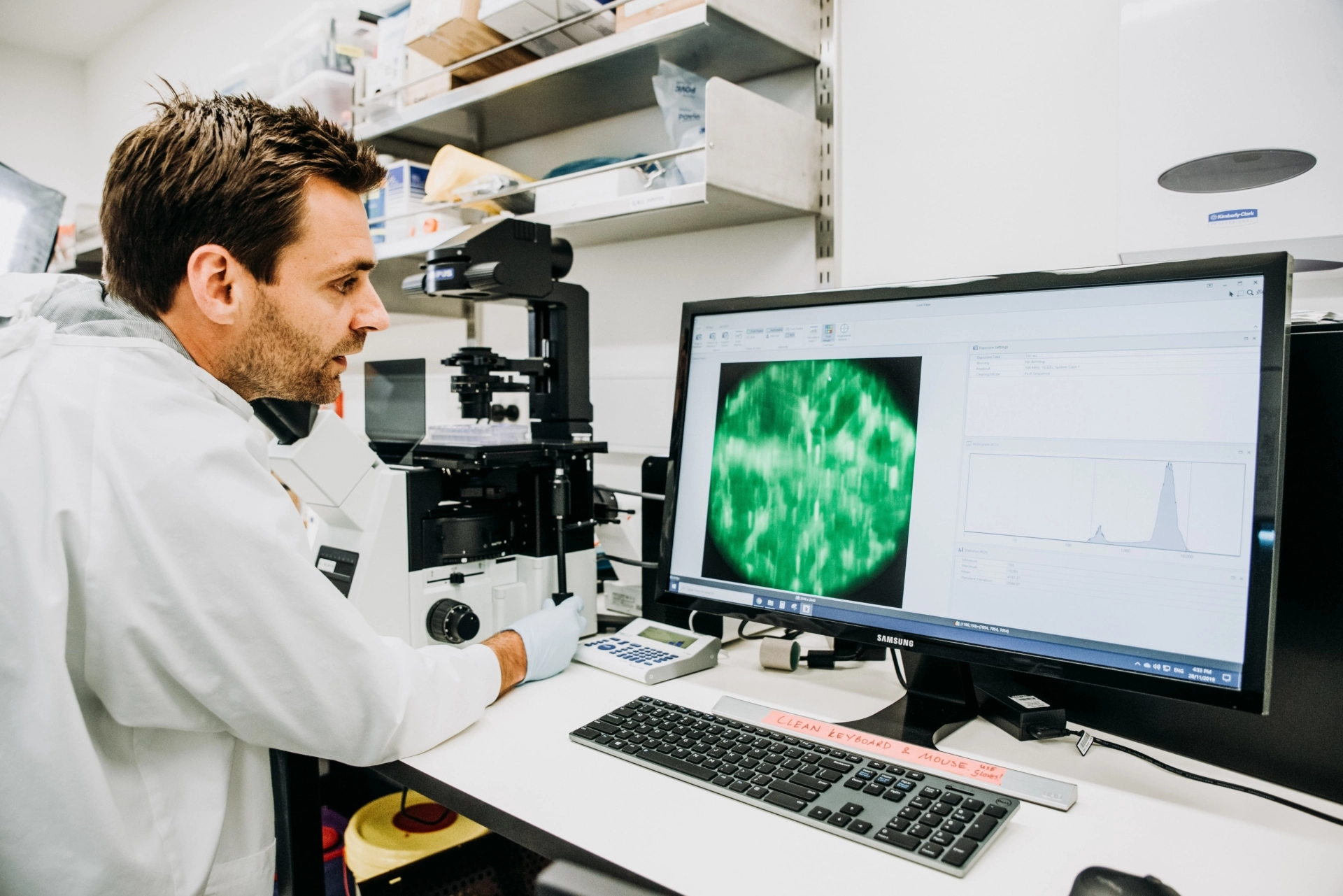

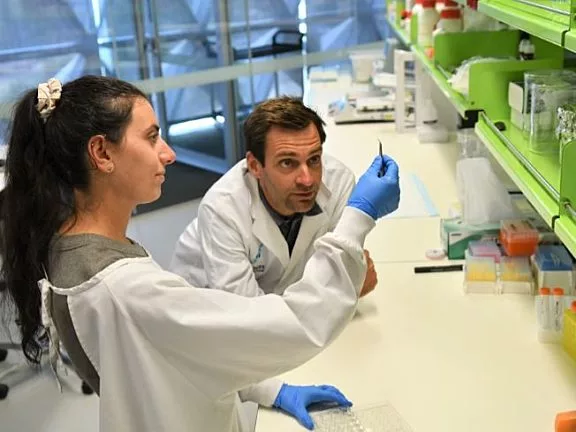

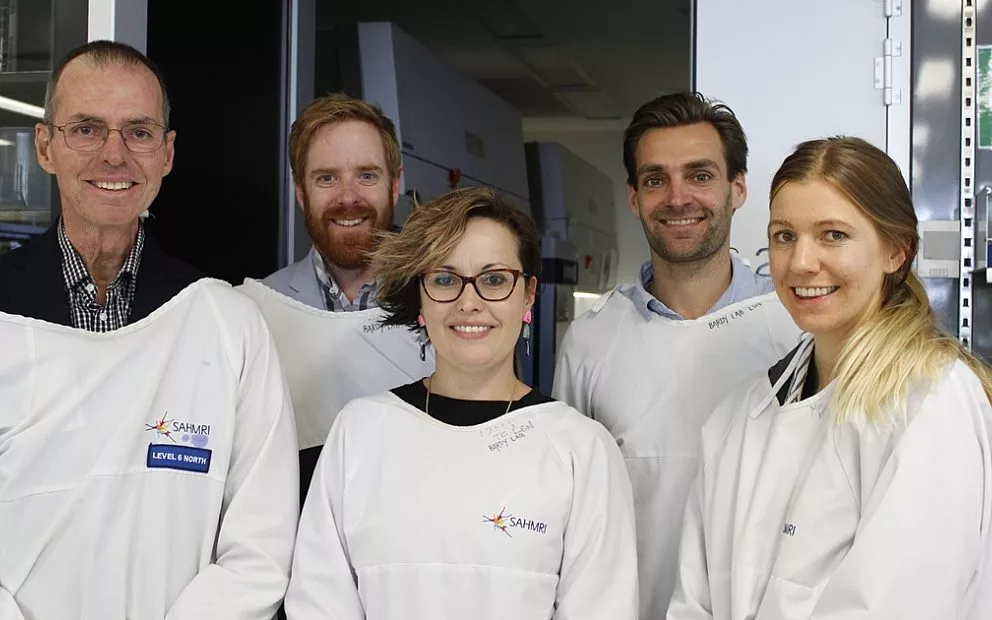

Associate Professor Cedric Bardy, from Flinders University and the head of SAHMRI’s Laboratory for Human Neurophysiology says his team has combined neuroscience and oncology to deliver hope of finding a new method to treat glioblastoma.

“Glioblastomas can affect anyone and only five percent of patients survive more than five years after their diagnosis,” he said.

“A major therapeutic challenge is the variability and adaptability of these brain tumour cells. From patient to patient, glioblastoma tumours are composed of several types of cells in varying proportions. It’s these variations and their incredible capacity to quickly change their identity to hide and escape treatments that make them challenging to eradicate.

“However, recent advances in genetics have shown that the cell types found within glioblastomas maintain some resemblance to the cells of origin, before they became cancerous, and use molecular pathways common with brain cells for growth and survival or when changing their identity.”

The study’s lead author Inushi De Silva, a PhD student with SAHMRI and Flinders University, says the team explores the cellular similarities and differences trying to shed light on the potential pathways used by tumour cells to escape treatment.

“What our research suggests is that we can learn from the genetics of healthy brain cells in order to target vulnerabilities in glioblastoma cancer cells,” she said.

“Brain cells are not as good as cancer cells in being able to quickly change their identity in response to environmental changes, so if we manage to exploit and amplify this hidden inherited genetic weakness in cancer cells, we might be able to reverse their ability to escape treatments.

“Glioblastoma cells are tough to kill because they are such a fast-moving target. This review helps us understand the different pathways in which they can hide. If we can block them in a corner, we may have a better chance to hit the target and cure this terrible disease.”

The authors say despite cancer cells having an immense ability to change and hide, the research shows they still evolve along known brain pathways.

“We should be able to use this in targeted therapy, with treatments that restrict glioblastoma tumour cells’ ability to change, known as plasticity,” A/Prof Bardy said.

“Understanding more about these mechanisms will be helpful to develop new treatments in the future. It is likely that effective therapies will be personalised and combine multiple agents, however knowing about the dynamic profile of glioblastoma cells, it seems essential to identify ways to block these identity shifts from occurring in the first place.”

The team is now testing potential treatments targeting subtypes of tumour cells that invade the human brain circuitry and are difficult to remove surgically, without harming the patient.

The paper ‘The neuronal and tumourigenic boundaries of glioblastoma plasticity’ is published in the journal Trends in Cancer.

A/Prof Bardy’s work has been supported by the NeuroSurgical Research Foundation.