It is no secret that there is a gender imbalance in science, technology, engineering and mathematics university courses and occupations. In Australia, only 36% of students taking STEM courses are women.

We had the privilege to interview two women currently working and studying in these sectors about what it means to be a woman in STEM.

Meet the amazing Claire and Sandra below!

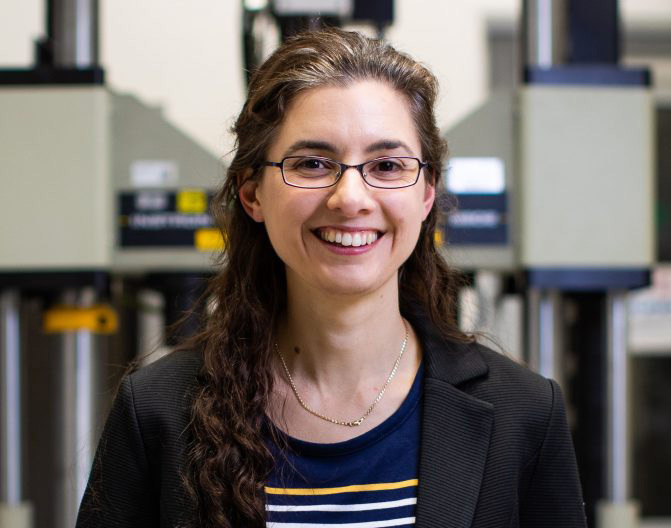

Dr Claire Jones

Dr Claire Jones is a Senior Research Fellow in the School of Mechanical Engineering, and the Centre for Orthopaedics & Trauma Research, The University of Adelaide, and an affiliate Research Fellow at SAHMRI. She leads a research group of staff and students with engineering and medical science backgrounds, and also collaborates with clinicians, vets and statisticians.

When did you first know you wanted to pursue a career in science?

As a child I would visit my Dad’s work, the Bioengineering Department in the basement of Royal Perth Hospital. I loved looking at the old medical and engineering instruments in the cabinets, and I thought orthopaedic implants were just fascinating. I was also interested in his area of expertise, Rehabilitation Engineering, which was integrating computer technologies for the first time (in those days) and designing custom equipment to assist people with limited mobility and function. My Dad’s colleagues always took the time to show me interesting things – hip implants retrieved from patients, big machines for mechanically testing orthopaedic implants, models of spinal deformities for surgical planning, custom plates to fix skull defects, and assistive technologies. My Dad worked directly with patients and had a profound impact on their quality of life. Although I don’t have that privilege, my research today has strong ties to orthopaedic, spinal and neurosurgery, and it’s unlikely I would have cultivated my interest without that early exposure to RPH bioengineering.

What are you currently working on?

My research encompasses various aspects of the biomechanics of neurotrauma (spine and spinal cord injury, brain injury), as well as orthopaedic and spinal research. Basically, I’m interested in how the musculoskeletal system works in a healthy person, how it is compromised with disease or disorders, and how it breaks during trauma. Projects currently being undertaken in my lab seek to understand: what causes the small joints in the back of the neck to dislocate during trauma; how the fluid around the spinal cord can help us to make surgical decisions for patients with spinal cord injury; how the brain moves and deforms inside the skull during a head injury; and how we can improve the design of spinal immobilisation training tools for paramedics.

What is your favourite thing about your current role?

By far the best aspect of my research life is working with amazing staff and students to solve really challenging problems. Injury biomechanics and neurotrauma research largely involves “modelling” real life accidents, and this is really difficult to do well; I enjoy the process of developing new models and methods to eventually answer really important questions about injury mechanisms. I work with colleagues, staff and students who have backgrounds in engineering, surgery, medical science, veterinary science, and statistics. No two days are the same!!

What is the most challenging aspect of what you do?

The most challenging aspect of my role is the lack of stability in employment, and inadequate research funding and inequity in funding allocations. This makes it difficult to resource projects properly, and leads to a lack of certainty and continuity of staffing. You definitely need to develop a thick skin to weather the rejection, and leading a research group can be stressful at times! I also work at the interface of two fairly male-dominated fields – mechanical engineering and orthopaedic surgery, which can provide challenges at times.

What changes, if any, are needed to make a career in science more attractive to women?

I have brought three amazing, gorgeous, children into the world in the last 6 years, and this has certainly changed my ability to work all-hours, pursue opportunities for travel and networking, and “achieve” at the same rate as colleagues in different life stages or situations. There is no easy fix, but changing the way we evaluate academic research performance and achievement, as well as improving the funding environment, will help women have equitable opportunity for a life-long career in science research.

Sandra Jenkner

Sandra Jenkner is a PHD Candidate at the Neil Sachse Centre for Spinal Cord Research.

When did you first know you wanted to pursue a career in science?

I knew that science was for me when I was about 8-10 years old – when I came to Australia, I read a tonne of books to learn English so I was quickly exposed to books about science. When I was 12 my sister started her degree in occupational therapy, so I started looking through her neuroscience textbooks, copied the diagrams, and became enthralled in the complexity of neuroscience.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently in my second year of my PhD, working on a project that focuses on the harsh inflammatory response after spinal cord injury, and how we can use stem cells to limit this inflammation and therefore rebuild lost neural cells better. This means that I am conducting extensive literature analysis about my topic, planning my experimental timelines, designing and optimising experiments to quantify my findings, and most of all: problem solving.

Did you have a role model that influenced your decision to work in science?

I don’t think I had a role model that I looked at and thought ‘yes, I want to be like her.’ Instead, I think what pushed me to consider a (challenging) career in science was the encouragement I received from my mother. We had a rough start to our lives in Australia when we moved here 16 years ago, but despite the challenges, the fact we couldn’t speak the language or the fact we didn’t start off with a lot of money, she made sure to encourage me in whatever I wanted to pursue (even if this meant buying 10 books a week for me).

What is the most challenging aspect of what you do?

Science and research is a volatile journey. Through much of my first year of my PhD, due to being a chronic perfectionist, I struggled with the fact that plans cannot be set in concrete and even when it seems like they are, they can still change very rapidly. Therefore, I had to learn to adapt to changes and do so quickly, navigate solutions, and make sure to aim my focus on ticking off current plans with only one eye set on the future.

What is your long-term research goal?

My long-term research goal is quite simple: conduct high quality research that is relevant, useful and novel to shine more light on my poorly understood research field. Although I am reserved in thinking I would be able to find a cure for spinal cord injury in my lifetime, it is my absolute joy to think that I could do something to make the lives of people with spinal cord injury a little easier.