Researchers from SAHMRI, SA Pathology and Adelaide University, have developed a new, highly targeted therapeutic approach that could improve outcomes for people living with myelofibrosis, a rare and serious form of blood cancer.

The research, published in the major international journal Blood, focuses on finding smarter ways to treat myelofibrosis by targeting the abnormal blood cells that drive the disease using immunotherapy, rather than just managing symptoms.

Myelofibrosis disrupts the body’s ability to produce healthy blood cells, leading to fatigue, pain, enlarged spleen and reduced quality of life. While current treatments can help relieve symptoms, there are no available treatments that remove them.

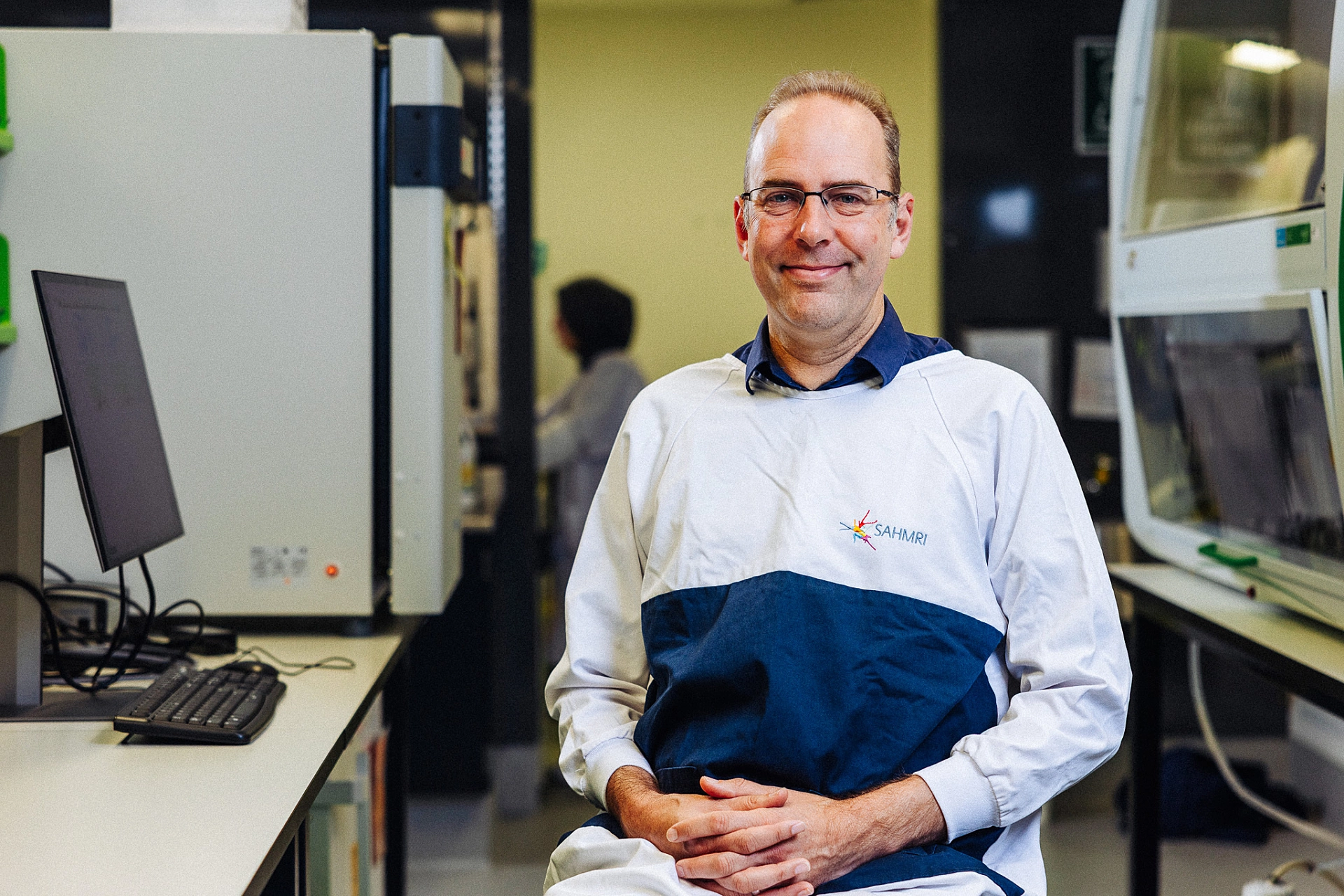

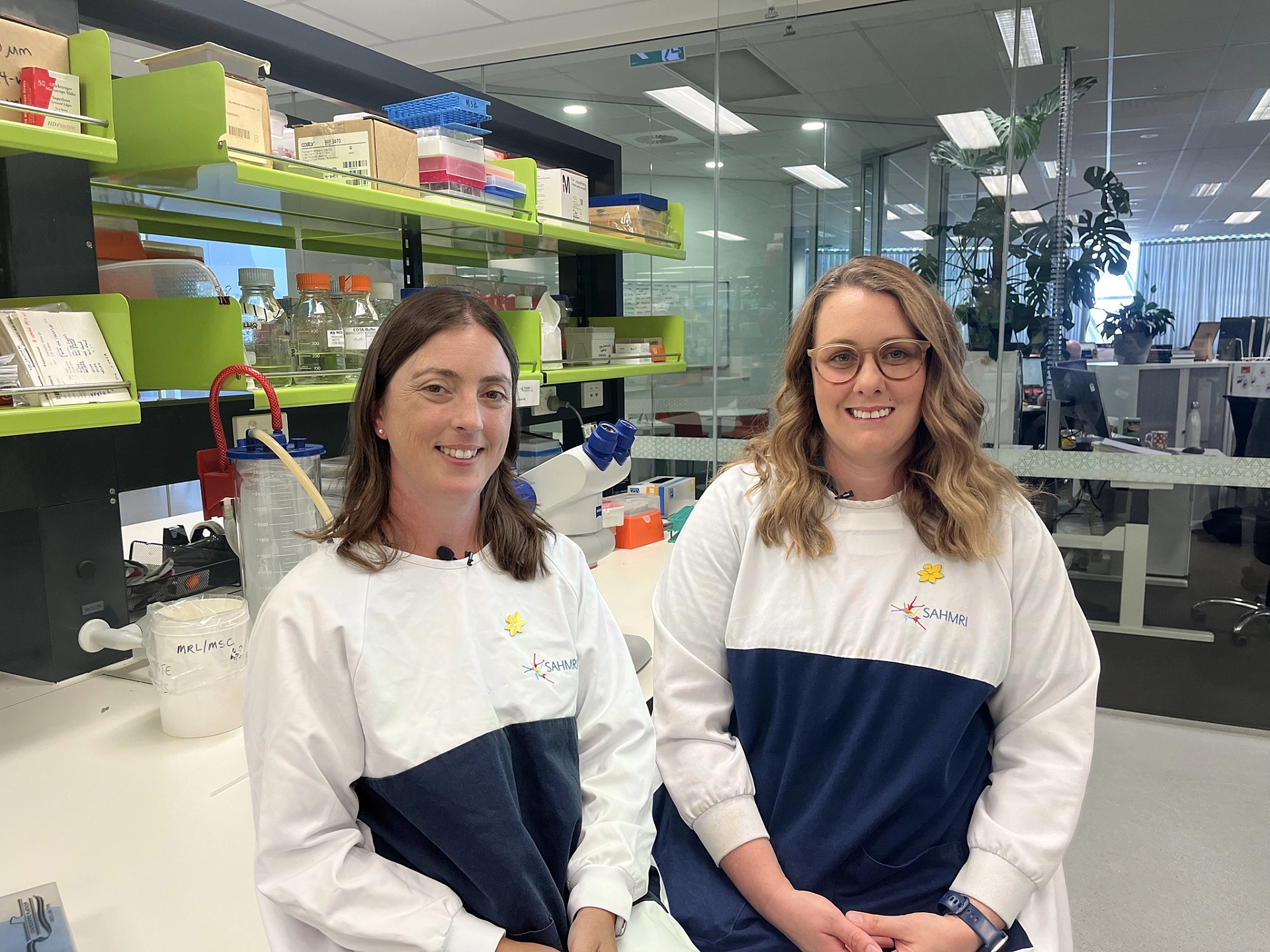

The study was co-led by Professors Daniel Thomas, director of SAHMRI’s Blood Cancer program, and Angel Lopez, Head of Human Immunology at SA Pathology, with significant contribution by Dr Denis Tvorogov from Adelaide University and Cancer Council SA research fellow, Dr Chloe Thompson-Peach.

Professor Thomas says the research represents an important step towards more precise, disease-focused treatments and is a world-first showing Type 1 calreticulin mutations differ from Type 2 mutations in terms of treatment.

The team found not just one, but two different targets that optimally remove the culprit cells. A vital and unique resource that led to the discovery were patient cells generously donated for research stored at the South Australian Cancer Research Biobank (SACRB), supported by the Health Services Charitable Gifts Board.

“People with myelofibrosis are often treated with therapies that help control symptoms, but they don’t selectively target the abnormal cells driving the disease,” Prof Thomas said.

“Our research shows that by focusing on what makes these cells different, it may be possible to develop treatments that are both more effective and more targeted. This is part of a major paradigm shift in the treatment of myelofibrosis and related diseases.”

The study highlights the potential of precision immunology, an approach that uses the immune system to recognise and act on disease-causing cells while leaving healthy cells largely unaffected. The findings suggest that different biological forms of the disease may benefit from different targeted strategies.

Professor Lopez says the work reflects a broader shift in cancer research towards smarter, more personalised treatment approaches.

“This work shows the power of precision immunology, where treatments are designed to recognise disease-causing cells with extraordinary specificity while sparing healthy tissue,” Prof Lopez said.

“The future of cancer treatment lies in understanding disease at a molecular and immune level and then translating that knowledge into therapies that are, potent, long-lasting and precise.”

While the findings are promising, further research and clinical development are needed before the approach can be tested in patients.

Cancer researchers will now work through the necessary steps to determine how this approach can be safely progressed towards clinical trials, with the aim of translating it into safer, more effective treatment options for people living with myelofibrosis as soon as possible.